Dream. Snap. Freedom: Interview with Victoria Vorobeva

Victoria Vorobeva is a London-based film-maker and videographer, currently working at Central Saint Martins, having graduated from London College of Communication earlier this year with a degree in Media. Victoria has always been fascinated by film-making as a tool of story-telling and uses experimental approaches. Having been introduced to Soviet cinema as a child growing up in Russia, Victoria credits these influences in her visual style and interpretation.

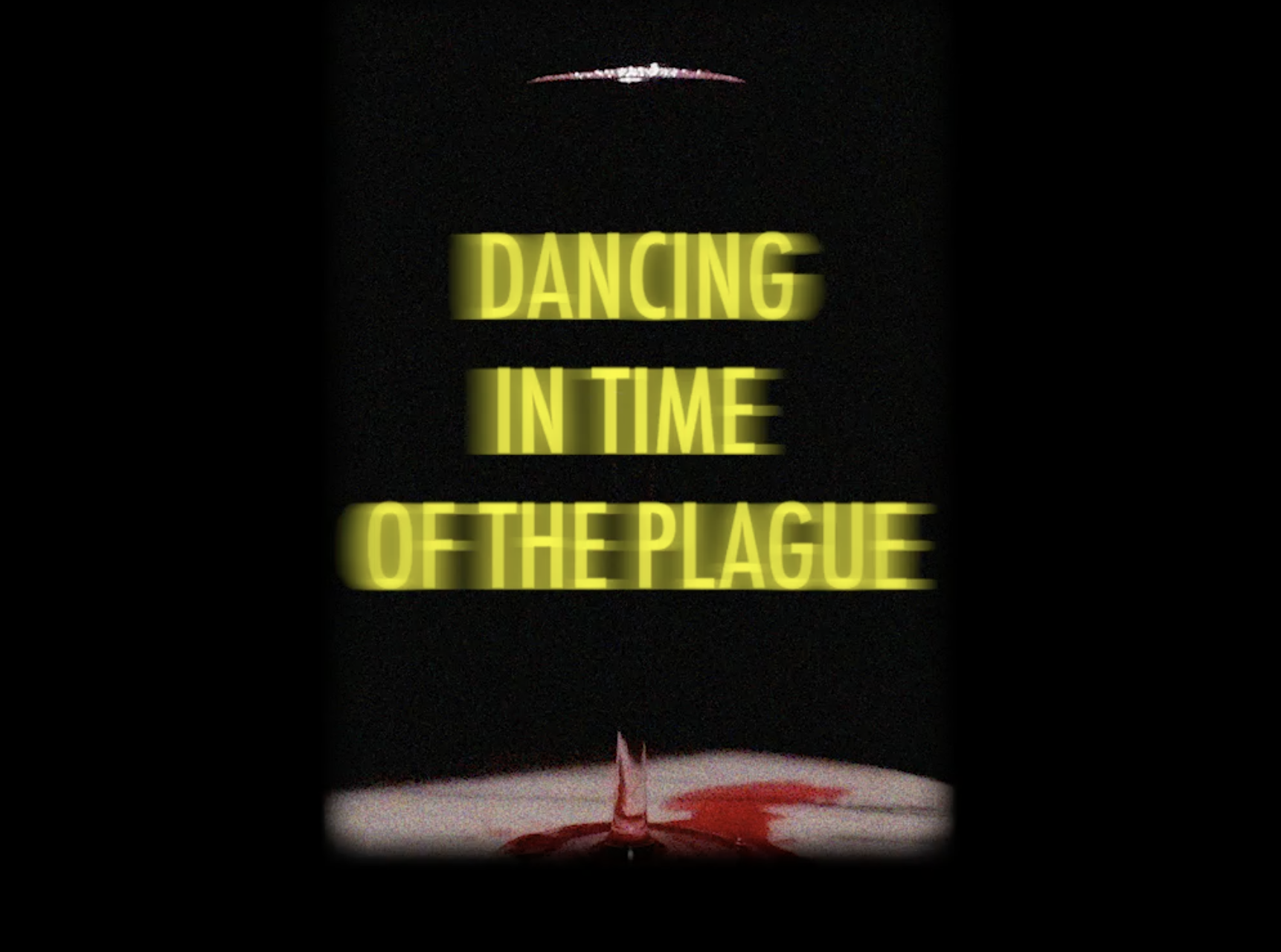

Victoria’s work ‘Dancing in the Time of Plague’ is a short film about dancing during a time of crisis. All participants in the film were asked to dance during the first lockdown in order to release their energy and let go of all the stressful and obsessive thoughts. Victoria’s main inspiration was the film Gaspar Noe’s ‘Climax’ where people lose themselves through a crisis only to then find themselves through dance. Her concept was not only to capture people dancing but also for them to feel completely free in how they dance, how they move, which music they choose, creating a therapeutic experience for them and a form of protest and rebelling against the daunting atmosphere within a fear-mongering society.

We caught up with Victoria to find out more.

Tell us about yourself

I was born and raised in Moscow, Russia, having moved to London in 2016 when I just turned 17. Being introduced to Soviet cinema I have always held a very high interest in film-making, especially in experimental visuals. I studied Contemporary Media Studies at London College of Communication where we were learning fundamentals of media theories through films.

What was the inspiration behind your work we've selected for Dream. Snap. Freedom?

The inspiration came mainly from Gaspar Noe’s ‘Climax’. I loved the honesty of dancers in his film and how genuine they were about what to do and what they love. That really intrigued me. The raw, explicit excitement about their passion - what a beautiful story.

I have also always been fascinated by the legend of the Dancing Plague that took place in the 16th century. People in a small village just danced for two weeks until they died of exhaustion. No one knows for sure what caused it but it’s simply wild to imagine what it all looked like. And then I was thinking how I could converge both of the topics.

What was the process behind this particular body of work?

All participants were free to choose any music, free in their movements and the way they danced. Some chose to just stare in the cameras as a close up, some chose a story-telling dancing style, some were just enjoying themselves. They were all telling their own stories in their dances and that’s what I was trying to achieve – everyone was protesting the exhausting reality and then showing me how they did it. I think this was the greatest part – that non-verbal communication that I have been able to achieve.

I chose sort of collage-looking editing style to turn all the participants sort of into the same energy, everlasting movement.

How your project has helped you and the people participating in your project during 2020?

I feel when the first lockdown was announced people were terrified. Everyone was suddenly out of their comfort zones coping with new rules and limits. London, such a free-spirited city turned to be a prison for so many people. I wanted people to just let go, feel free even if it was just for 5 minutes of their dance and enjoy themselves, their music, their moves. I think letting go has been so underestimated recently, in a sense, that if you want to let go - do it, you want to do a stupid dance in front of the mirror - why not? At the end of the day we need to take care of ourselves and it’s the only thing that matters.

What has been the public reaction to your work?

The public’s reaction was very welcoming. As well as everyone who took part in the video was very eager to participate and I have positive feedback from them as well.

What would you say the role of the photographer or film-maker is within activism?

The messenger. Creatives have all means of turning relevant issues into something that will catch someone’s eye. The artists don’t necessarily offer any solutions, but they suggest you look at the core problems from different perspectives and angles and I believe the more sides are seen - the more solutions can be found in the end.

What would you say is a form of Radical Play?

I feel that in my particular project I wanted to depict activism not as a form of protest but rather as a form of liberating oneself. Since the main influential factor in my work was the pandemic, I wanted people to protest or rebel against the feeling of being held a prisoner because of fear. I wanted people to break their own barriers of being uncomfortable with the situation and find the light in it.